Dunhill - Namiki [ダンヒル - 並木] (1918 ~ today)

HISTORY

Ryosuke Namiki

A maki-e pen by Koichi from Namiki Co.

Gonroku Matsuda

Dinner party that followed signing of distributor contract with Alfred Dunhill.

Signature: Koho Iida [光甫], 3.3x4.5 cm.

Namiki Fountain Pen Making Process

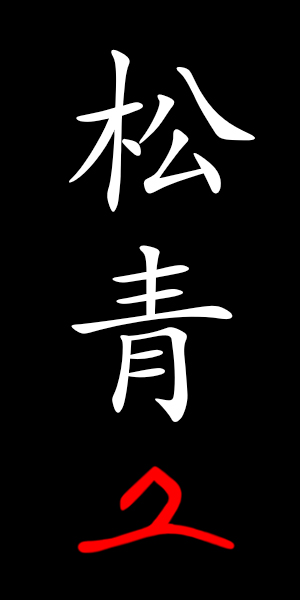

A common mark looks like:

where:

1. right column usually reads "並木监" ("Namiki-kan" - "Supervised by Namiki") or

"國光會" / "国光会" ("Kokkokai").

2. left column consists of an individual artist signature ("Mei") followed by

3. a personal monogram or seal of an artist in red ("Kao").

There are basically three levels craftsmanship in the lacquer art, starting with those who prepare the base material, then the preparers of the lacquer surface, and finally the highest, the makie-shi, or decorative artists. Today there are many independent artists, but in the past the makie-shi were part of a guild. Here, artists or associates worked under the guidance of the master, making the designs, while the artisans, namely the apprentices, worked only on preparation of the surface of the object to be decorated. The finest craftsmen also manufactured complete decorations, but they had no power of signature: they could sign their works only when the master promoted them from artisan to a full guild member. The members were divided into seniors and juniors, and the latter could sign their works using only the name of the guild, while the former could use their name (“Mei”), which was added next to that of the guild, or their monogram (“Kao”), next to the name.

Marks

Individual marks of artists from the Namiki company

Advertisements

Examples (from the web)

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|---|